‘Neo-necrophilia’ and the Rise in Romantic Revenants

“Love never dies, but lives immortal Lord: If love impersonate was ever dead,

Pale Isabella kiss’d it and low moan’d; ‘Twas love; cold – dead indeed – but not dethroned”

– Isabella or The Pot of Basil, Keats

The current abundance of the undead in popular literature and on film poses the question: what factors affect trends such as these? I find it interesting that undead ‘anti-heroes’ become heroes during specific zeitgeists. Not only does their prevalence increase, they develop new characteristics which fulfill requirements of the age, thus satisfying time specific needs and becoming more desirable. Is this a type of evolving necrophilia or ‘neo-necrophilia’?

In this post I will look at the parameters which encompass necrophilia according to psychologists. Then I’ll examine previous necrophilic symbolism in literature and what it represents. Finally I’ll summarise by illustrating the reasons I think we have a need for this metaphor.

Necrophilia or ‘love of the dead’ is a rare paraphilia which, in the DSM-IV-TR is included with other paraphilias a a type of fetishistic behaviour. With the advent of the new DSM-V, this categorisation remains the same as there are no new data on this topic. [1] Originally it was grouped into 3 categories by Rosman and Resnick in the 1980, one of which was Regular Necrophilia which always amuses me: “Oh you know, I’m just one of those boring, regular necrophiles…” Another category was Necrophiliac Fantasy which often gets confused with their Pseudo-necrophilia category. For this reason, one of the most prolific writers on the topic Dr Anil Aggrawal has proposed 10 new categories to avoid confusion [2]; ‘Class I’ encompassing role players and ‘Class III’, fantasizers. Despite the fact that these two groups have never and will never touch a cadaver, let alone have sex with one, they are still psychiatrically speaking classed as necrophiles which illustrates the concept of necrophilia continues to evolve. The romantic desire to be with a revenant such as a vampire or zombie can fit into these categories, and that idea is nothing new. It has been said of Buffy Summers’ sexual encounter with Angel in Buffy the Vampire Slayer that it was presented as “a natural culmination of their love for each other. That she was technically making love to a corpse was overlooked” [3] Of course there are some glaring differences between vampires and the usual idea of a dead body.

In Twilight, the book which spawned a million imitations, Edward Cullen walks and talks, and most corpses (as far as I’ve experienced) do not. Sexy vampires such as the Cullens and those in True Blood aren’t inanimate of course, but they encompass the motifs of incorruptibility and perpetuity which cadavers do in early necrophilic literature. I’ll discuss the significance of that later on.

More interestingly, the main character and romantic revenant in the book/film Warm Bodies is a zombie called merely ‘R’ – dehumanised by the fact he doesn’t even have a name. He can move but he can’t talk, so he’s one step up from a cadaver and one step down from the Cullens. Despite the fact he’s a monosyllabic zombie (or maybe just a typical teenage boy?) the lead human female character falls in love with him anyway.

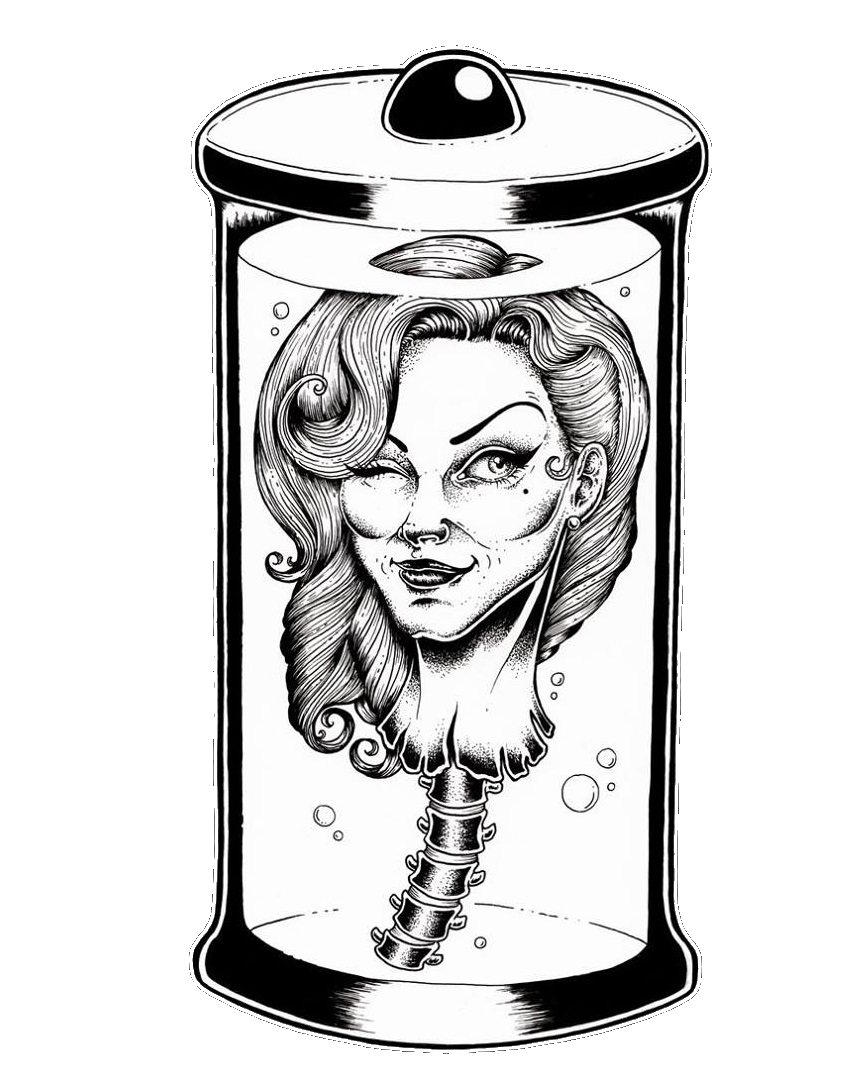

Before I begin to describe this current trend in paranormal romance as ‘neo-necrophilia’ it’s helpful to explore the theme in earlier literature such as 19th Century Decadence. In these works, characters did have sex with corpses, but much of the time this physical act was an allegorical statement made – literally – flesh or “A theme testifying to the strength of a passion which defies corruption and endures everlastingly [4] The motif can even be seen in stories such as Boccaccio’s Lorenzo and Isabella which became a poem by Keats, part of which is at the beginning of this article. In the story, Isabella removes the head from the corpse of her murdered lover Lorenzo and keeps it in a pot of basil which she waters with her tears. I discuss it more in another post.

Another theme from literary necrophilia is a projection of our own fear and a sense of attempting to come to terms with our own mortality by overpowering and fetishising it. Elizabeth Bronfen calls it “…a figure of fear and desire for death projected onto the body…”

Using the above two motifs we can argue that the romantic revenants of the current popular genre are fulfilling the same needs – they are incorruptible, they endure, they are immortal and therefore comfort us that perhaps we can overcome our own mortality. In fact, if most 19th Century Decadent literature featuring necrophilia has in common the theme of downplaying the reality of physical decay, it can be said that modern works simply eradicate that notion entirely. Warm Bodies goes one further and the main character, zombie ‘R’ is actually cured of his condition of being ‘undead’ – the putrefaction is once he falls in love.

It is this stability, this unchanging nature of the idealised corpse or articulate undead which I think is key to the genre’s recent popularity. In times of social upheaval there is a safety in these creatures who exist ‘outwith society – they are not subject to the whims of a tumultuous world and as Bella keeps re-iterating in Twilight “An accident could just come along and tear us apart.” They are also not slaves to their own biology and the problems that are associated with that too. In Warm Bodies, ‘R’ who can think (although he can’t speak) muses “It’s one of the perks of being dead, another thing we don’t have to worry about any more. Beards, Hair, toe-nails…no more fighting biology. Our wild bodies have finally been tamed” Psychological literature on necrophilia affirms that a morbid attachment to the dead is motivated, in part, by the removal from the realm of interpersonal conflict and perhaps the same can be said for external conflict. Aggrawal states that one of the main motivations of necrophilic behaviour is “seeking stability and security.”

Evidence of this need for collective stability can be seen in the timescales of the current genre’s popularity. The book Twilight was published in 2005. It did do well and reached number 5 on the bestseller list by 2006, but only reached number 1 (becoming the biggest selling book of the year) in 2008 – one year after the film was commissioned in 2007 as someone could see its potential, and 2007 was the year the term Credit Crunch was first used, and the year we were all being bombarded with the news we were entering a recession.

In fact prior to that there was already an atmosphere of fear. The number of Paranormal Romance novels featuring these undead, incorruptible protagonists doubled between the years 2002-2004. That came after one of the largest cataclysms the Western world had really known for many years – 9/11 in 2001. It’s also stated by scholars that the 1980s spike in Vampire movies which are ostensibly the ones which gave us the sexier characters – Lestat, Louis and many of The Lost Boys – occurred in response to the new AIDS crisis.

So perhaps it is fear which births this need for stability, and those already dead appeal because they can’t be harmed – they are perpetual and stable vectors for our projected panic. In a Western society which doesn’t experience enough of its own dead to understand the processes of putrefaction, this idealised notion of death is paradoxically a comfort. And as definitions of necrophilia evolve, this type of revenant worship in a romantic context could be seen as ‘neo-necrophilia’ for want of a better term.

Refs:

[1] “The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified”, Martin P. Kafka, American Psychiatric Association 2009

[2] “A New Classification of Necrophilia”, Anil Aggrawal MBBS, MD, Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 16, 2009

[3] “Necrophilia and S&M: The Deviant Side of Buffy The Vampire Slayer”, Terry L. Spaise, The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol 38, No. 4, 2005

[4] “Necrophilia and Authorship in Rachilde’s La Tour d’amour“, Robert Zeigler, Nineteenth-Century French Studies, Vol 34, Number 1&2, Fall-Winter 2005-2006

Pretty! This has been an incredibly wonderful article.

Thank you for providing this information.